Afference: The Silent Killer

Afferent coupling, or afference is the vice that holds your design in place and keeps it from changing. It’s like cement poured around your code and allowed to harden. It calcifies your codebase, keeping you from the productivity you know you should have.

You know in your bones that software development should be easier than it is, that it should be less tedious than it is, and should not be so fraught with setbacks and obstructions to progress. Much of this strife is rooted in afference. Especially unmanaged afference.

The elements of your codebase that have higher afference are the ones that you’re not free to change. Keeping afference (and really, all design principles and qualities) foremost in your mind while you’re writing code will keep you from adding new setbacks and frustrations to your work, and keep the existing ones from getting any worse.

What Is Afference?

Afference is the inbound coupling of some unit of software, be it a module, a class, a function, a library, a package, an interface, a system, or even a variable.

Inbound coupling means: uses of some unit.

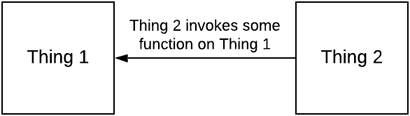

In the following diagram, a unit (ie: class, object, function, module, library, package, etc) named Thing 2 is invoking some function/method/procedure on Thing 1.

That invocation that is inbound to Thing 1 is the afferent coupling.

From the perspective of Thing 1, that invocation is afference. Meanwhile, from the perspective of Thing 2, the invocation is efference.

Inbound coupling is afference. Outbound coupling is efference. Any invocation or call has both afference and efference.

The thing that is invoking a call is the efferent, and the thing receiving the call is the afferent.

A good way to remember the difference is to reflect on the meaning of the words affect and effect. You are affected by something that acts upon you. That thing doing the act is effecting the act.

The Problem With Afference

Software is largely useless unless some unit of software is invoking some other unit of software. Things calling other things are necessary and inevitable.

The problem arises from unmanaged afference, and from putting afference in the wrong place. Like cholesterol, there’s good afference and bad afference. Or more accurately, there’s safe afference and there’s dangerous afference. There’s afference that’s going to harm your ability to make progress with your codebase, and there’s afference that won’t.

When it comes time for you to make a needed change to that function on Thing 1, you may also need to make changes to all users of that function on Thing 1. Which means that changes to Thing 1 are likely to cause needed changes to Thing 2.

In the contrived example of Thing 1 and Thing 2, it might not be such a big deal. It depends on whether there are secondary effects to Thing 2. For example, if the call to Thing 1 requires that Thing 2 changes aren’t just limited to internals, but that Thing 2 requires changes to the arguments passed to it, then users of Thing 2 will also require changes. And so on and so on and so on.

This kind of cascade of changes is a sign of another, pre-existing design flaw where other basic design principles and qualities were neglected, and are being amplified and exacerbated by the addition of inappropriate afference to an already-problematic design.

This simple use case of one piece of software coupling to one other piece of software isn’t an entirely realistic representation of the reality facing most software developers.

This situation may not be much of a setback:

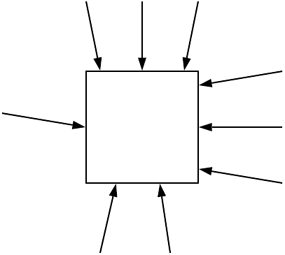

But such an overly-simplified situation is not the kind of pervasive problem that stops software developers and projects in their tracks. Typically, the kind of afference problem that software developers face looks like this:

The software sickness is intensified and aggravated when the obvious design mistakes aren’t recognized to begin with or are naively disregarded as “negligible”, and are further entrenched by continuing to build new software upon the mistakes rather than making corrections immediately when problems are identified.

Anything built upon a weak foundation is also weak. And in software, everything is potentially the foundation of the next thing that gets built.

In software, anything can be the foundation of anything else. Avoiding this state is one of the principle concerns of software design; it’s principles, qualities, processes, and patterns.

Implications of Afference

When developers come face-to-face with some work that they need to do on some piece of software with high afference, their motivation for the work wilts.

Software with high afference typically also suffers from afflictions that have accumulated much more intensely as a result of design flaws migrating along lines of communication and coupling.

By the time a developer comes along to make what would ordinarily be a straight-forward change, they’re stopped in their tracks in the face of entanglements between other pieces of software that interact with the one needing to be changed.

This is the cement that keeps software from changing. This is the calcification that keeps developers from being able to do their jobs in as straight-forward a manner as would be expected. And this is why software projects lose momentum over time rather than maintain or accelerate their pace of progress. And subsequently, this is why there’s so much staff turnover in software development.

Developers simply arrive at a point of maximum despondency with the codebases they they’re tasked with, and they start to look for greener pastures. And tragically, when a developer finds a greener pasture, what do they often turn around and afflict this healthy software with the same old software cancer that they were trying to escape to begin with.

Afference is never so insidious as when afference on a flawed design is allowed to increase as new software is built upon mistakes. This is how software developers tie their own hands and lock themselves into entrenched design mistakes that are the source of their counter-productivity.

What You Can Do About It

The first step to bringing harmful afference under control is to simply practice being aware of afference in every moment of your work life as someone who is at risk of creating yet more of it. As a developer, it’s in your hands. Vigilance and awareness is the first step.

Just make it a Big Deal. And you should, because it is indeed a big deal. Put it foremost in your mind and then you’ll be reminded of it while you’re up to your elbows in code. If you’re a developer who is prone to forget about the things that you’re supposed to remember, consider making yourself a checklist, and keep it in sight on your workbench.

You must also gain a grasp of which kinds of afference are safe and which are dangerous. Not all afference leads to exacerbated counter-productivity. It’s only when some piece of software becomes highly afferent that shouldn’t be highly afferent that the problems start.

The obvious implication here is that some pieces of software can afford to be afferent, and that afference will have a minimal impact on productivity, and some pieces of software absolutely cannot afford to be allowed to become highly-afferent. It’s critical to put afference where it belongs and where it can do less harm. It has to be something that is entirely under your control as a developer.

Afference is safe for generalizations and general purpose things, but dangerous for specialized things and special purpose things. The underlying principle is that things that don’t change at all or change very infrequently can afford to have high afference, and things that change frequently are likely to be highly efferent, and therefore should not also be afferent.

For example, a scenario-specific thing like a web controller is a special-purpose thing. It’s only used when serving the specific use case that it implements. It is not expected for something like a web controller to be afferent. It coordinates and invokes other things that are enlisted to carry out some web request. It’s efferent. It’s relatively easy to change the code in a web controller because most of its communications are outbound. Most changes to a web controller are changes to internal logic.

On the other end of the spectrum, something like the a language’s ultimate base class, like Java’s System.Object class or Ruby’s Object class, are highly afferent. Absolutely everything in the language is coupled to these apex classes. They are highly afferent, and like things that are highly afferent, they are not expected to change - at least, not without some formality of process.

Conclusion

Afferent parts of software aren’t amenable to change, so parts that are expected to change should not be afferent.

Afference is unavoidable, but it’s manageable. And managing it is a critical component of keeping your project from turning into the tedious drudgery that we all want to avoid in our work lives.

It’s not the existence of afference that kills software development productivity, it’s putting afference in the wrong parts of the design: the parts that are expected to change.

Just by keeping an eye on afference, and conditioning yourself to be aware of it and where you’re putting it, you’re at least a step ahead of its worst effects.

Scott Bellware

Scott Bellware